Seeking the stories our objects can tell

Dr Sumner Braund continues her exploration of the Islamic instruments in our founding collection, confronting the impact of European colonialism on how we tell their stories.

Tracing owners through time

In my first blog post, I introduced the Finding and Founding Project to investigate the provenance of our founding collection, donated by Lewis Evans in 1924.

It was significant for many reasons, not least because, within his collection, Evans had assembled a group of precious, historically important instruments from the Islamic World.

The Finding and Founding Project is investigating how Lewis Evans acquired these objects from the Islamic World.

But why is it important for the Museum to uncover who owned these instruments before Lewis Evans?

History in a single object

The provenance — or ownership history — of our collections is a crucial part of the rich histories they can tell.

We can learn a lot of history from just one object — in fact, a single object can open windows onto many people and places in the past.

The traditional way to investigate museum objects is to focus on the ‘who, ‘when’ and ‘where’ of their original setting.

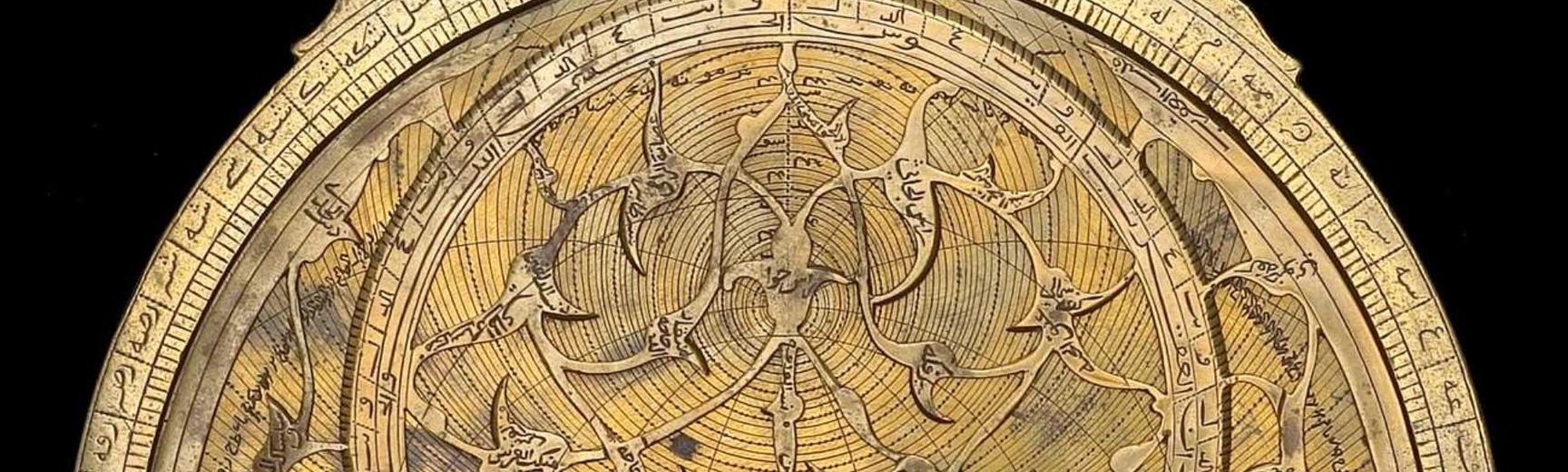

Let’s take, for example, this South Asian astrolabe from the 1600s CE:

Complete front

Complete back

Mater

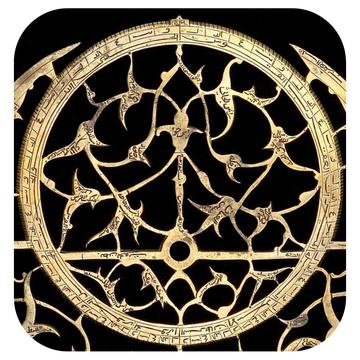

Rete

Astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad, Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

Who

The inscriptions highlight the name of the maker, Diya-Ad din Muhammad. His signature shows us that he wanted his knowledge and craftsmanship to be remembered. It also reveals his desire to position himself in a long, illustrious line of astrolabe makers.

The inscription positioned above the shadow scales reads:

‘The work of the humblest of the servants, Diya al-Din Mohammad, the son of Sheik al Haddad the Royal Astrolabe maker, the son of Kasim Mohammad son of Mulla Isa of Lahore in the year 1069 AH.’

Astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad, Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

When

It was made in the late 1650s CE — during the reign of the emperor Shah Jahan — in Lahore, a favourite city of Mughal royalty.

A window onto a time and place in history, this complex astronomical instrument points us to the sophisticated and wealthy intellectual circles operating in and around the Mughal court.

The intricately worked throne and rete reveal refined aesthetic tastes; swirls of flowers and vines hint at the joy in nature found in the lush courtyard gardens beloved by Mughal emperors and nobles.

Throne of astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad

Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

Detail from rete of astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad

Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

Astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad, Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

Where

The interior of the umm (mater) is engraved with the latitudes and longitudes of 92 cities and classified according to climate. It reveals cosmopolitan owners who were connected — economically, socially or intellectually — to places across the Eurasian continents.

The interior of the umm (mater): three concentric bands are engraved with names of 92 cities

Close-up detail of the umm (mater)

Astrolabe, by Diya al-Din Muhammad, Lahore, 1658/9 [1069 AH] Inv: 53637

But this was not the only world in which the astrolabe operated.

Nearly four thousand miles — and over four hundred years — from its origins, this beautiful scientific instrument is now on display in the History of Science Museum’s Top gallery.

We are on the hunt to discover:

- How did it get from Lahore to Oxford?

- What was its journey in the intervening centuries?

- Who owned it?

- Why did they want it?

- What did they use it for?

And we know the answers we find along the way may be complex to uncover, and uncomfortable — even shocking — to hear.

A “winner’s” window on history?

Our own Museum is the final link in a chain of ownership. We see our role today as custodians — as much as owners — of the objects in our collections.

That's why we should ask the same questions of ourselves as we do of past owners, starting with: why does the History of Science Museum have these objects?

In uncovering the answer, we have to confront the role that Museums — including ours — have played in the last 250 years of world history.

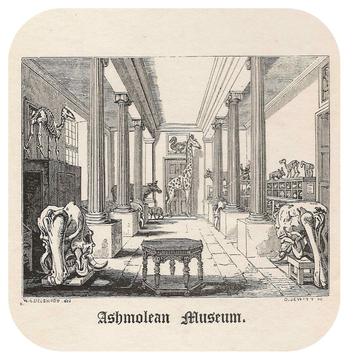

Pencil Drawing (Framed) of the Middle Gallery of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, by W. A. Delamotte, c.1836

History of Science Museum (Old Ashmolean building) Top gallery c. 1951

Most European museums founded in the 1800s were — implicitly or explicitly — products and tools of colonial violence.

In many of these museums, ‘World history’ galleries displayed the cultural heritage of societies oppressed by European colonisers.

In some of the galleries, precious pieces of cultural heritage were framed as evidence of ‘uncivilized’ people; in others, they were displayed as models of craftsmanship that could stimulate European innovation. The idea was that European industrial production would take inspiration from — and then surpass — these models.

By exhibiting the spoils of colonialism in various different forms, 19th-century European museums functioned as powerful apologists for colonial regimes, justifying the aggressive extraction — and dehumanisation — of cultural artefacts from societies around the globe.

So how have museums founded in the 1800s started to break the cycles of violence in which they themselves have taken part?

A first step has been to critically interrogate their own origin stories.

Colonial encounters

History of Science Museum, Broad Street, Oxford

Founded in 1924, the History of Science Museum (formerly the Museum of the History of Science) came into being at the height of the global British Empire.

Lewis Evans bought many of the precious scientific instruments from the Islamic World in our founding collection when they were circulating through European art markets in the 1800s and early 1900s. These instruments were on sale as a direct result of economic encounters in the Empire — and violent colonial extraction.

The Museum’s founding helped establish the importance of History of Science as an academic discipline. And down the years, we have exhibited objects in a way that has reinforced the scientific advances which European men have achieved.

But what about women's contribution to science? And the contributions made by the original makers and owners of the instruments from the Islamic World?

Listening to our objects

In 2014, we started the important process of uncovering the full spectrum of stories these collections can tell.

Today — nearly a decade later — you can take a wander through our Basement and Entrance galleries to find objects highlighting the ground-breaking contributions made by women scientists.

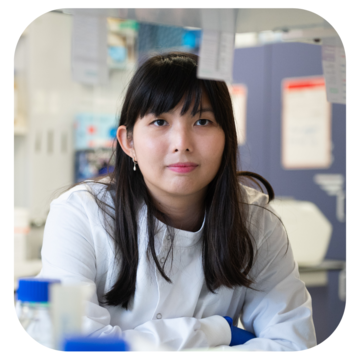

Dr Carina Joe, Senior Postdoctoral Research Scientist in Vaccine Development and winner of a 2021 Pride of Britain Award for her work on the OxfordAstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine

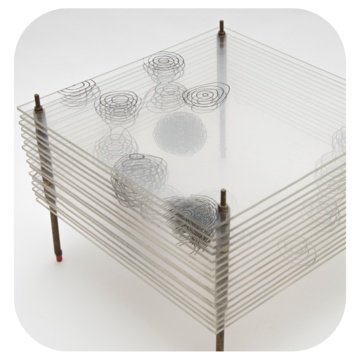

Model of the Structure of Penicillin, by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, Oxford, c.1945. Professor Hodgkin remains the only British woman scientist to win a Nobel prize in any of the sciences.

And in our Top gallery, you’ll discover qibla indicators and astronomical instruments which, for Muslim researchers today, represent the intersection of religion and science.

These are important stories — and there are so many more to tell.

That’s why the Finding and Founding Project is such a vital step towards uncovering our own colonial past by listening to all the rich, diverse histories embedded in our objects.

In my next post in the series, I’ll start sharing some of those stories.

April 2023

About the author

Dr Sumner Braund

I’m a historian of early medieval England with a passion for museums and archives.

As Research Fellow on the Finding and Founding Project, I am putting investigative skills to work as I uncover the provenance history of the History of Science Museum’s founding collection.

This work has already taken me to archives in the UK and the US, from nineteenth-century letter collections to sales registers to military dispatches.

For me, history is the study of people – and the objects that I am currently investigating are taking me on a global journey to people past and present.

Share on social media

If you'd like to share this post on social media, just copy this link:

https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/finding-and-founding-blog-two-seeking-the-stori...

and go to your chosen social media channel:

Comments

As always, we’re interested to know your thoughts, so please share your comments with me: