Making your mark: the Comtesse de Lespinasse’s Astrolabe

From powerful Sultans to a French countess, Dr Sumner Braund tracks down the owners of a rare Mesopotamian astrolabe, exploring the marks they left — and the price they paid.

How much would you pay for an 800-year-old astrolabe, inlaid with gold and silver and beautifully engraved with the constellations of the zodiac?

In 1911, the Comtesse de Lespinasse thought that £1,000 (equivalent to about £108,300.00 today) was a fair starting price.

The Comtesse’s astrolabe was not only beautifully constructed and very old, it also had a connection to Saladin — one of the most well-known medieval Muslim rulers of the Ayyubid dynasty.

Surely, £1,000 couldn’t even begin to cover the instrument’s historic significance?

Lewis Evans disagreed.

How did the Comtesse acquire the astrolabe?

The Comtesse de Lespinasse was born Louise Marie Robertine Maillard de Liscourt, the daughter of a respected army officer in Napoleon I’s court and niece of the vivacious Madame de Caze, another notable courtier.

Louise Marie became a countess in 1846 when she married Louis Charles Lespinasse, Comte de Pébeyre. On the occasion of her marriage, her parents and aunts showered her with gifts.

Le Château Pébeyre, home of the Comtesse de Lespinasse. Image from Alienor, Conseil des musées

Her marriage contract, which survives in the Archives nationales of France, reveals that Louise Marie’s family provided her with a generous inheritance. They also made sure that everything given to her as wedding presents – linen, china, silverware, paintings, antiques and, just maybe, an 800-year-old astrolabe – would remain hers alone to keep.

Whether it was a wedding gift or a purchase made during her marriage, the astrolabe was unquestionably Louise Marie’s – not Louis Charles’.

In 1900 the astrolabe was exhibited under her name at the World Fair in Paris – the Exposition Universelle.

In July 1902 – four months after her husband's death – she arranged for it to enter an auction at Christie's in London (although the sale does not seem to have gone through).

The inventory of Louise Marie and Louis Charles’ home, Château Pébeyre – taken by the local magistrates of St Pardoux-la-Croisille in March 1902 – detailed every piece of china, furniture, painting, and linen cloth in her late husband's estate.

Louise Marie must have followed them from room to room: every so often, the clerk carefully noted that an object in his list – a Louis XVI bronze balance, a porcelain teapot, a bronze cup mounted on a marble pedestal, amongst many other things – belonged to Louise Marie specifically, and not the estate.

The astrolabe was not listed in this inventory.

Where was Louise Marie keeping it?

Owners leave their mark

Louise Marie was not the only owner to prize this astrolabe.

The instrument's first owner was Al-Ashraf Musa Abu’l-Fâtih al-Muzaffar ad-Din. Nephew of the great Ayyubid ruler Saladin, Al-Ashraf Musa ruled in Mesopotamia in the early decades of the 1200s CE.

I hope he treasured the object that Abd al-Karim al-Misri spent so many hours making in the year 1227/8 CE [625 AH].

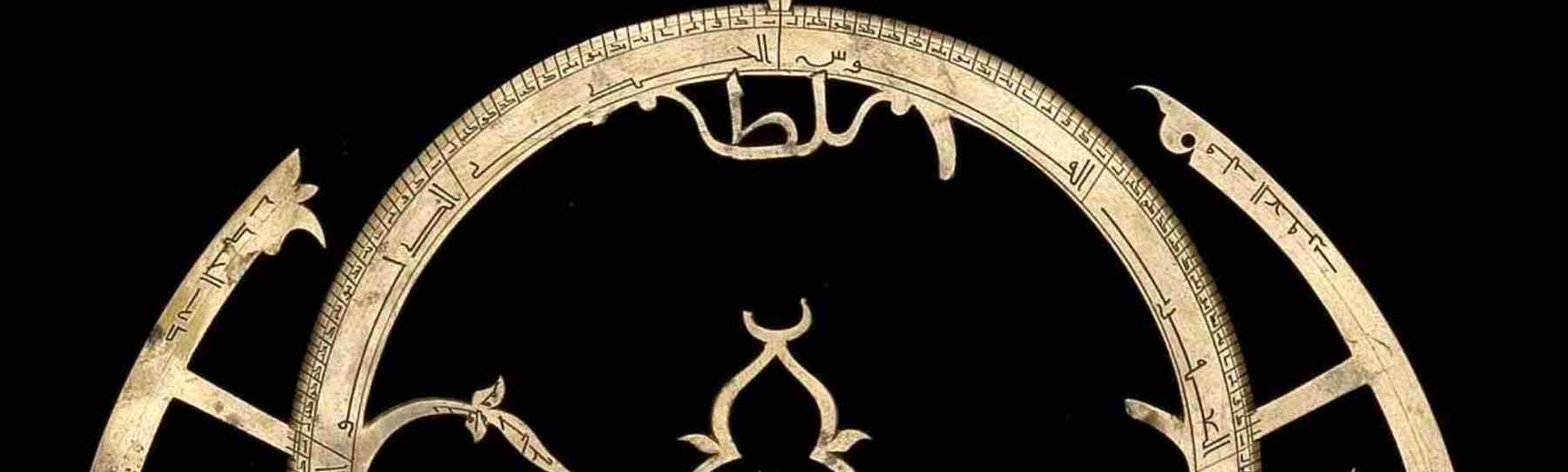

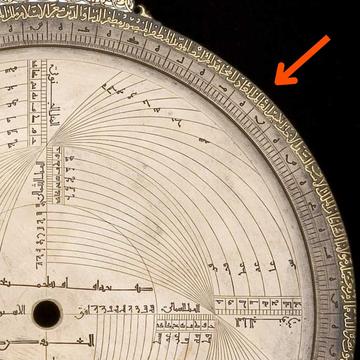

This talented craftsman celebrated Al-Ashraf Musa’s power and lineage with a lengthy inscription, inlaid in gold, that circles the rim of the astrolabe.

Inscription around the rim of the mater is gold inlay and celebrates with Al-Ashraf Musa Abu’l-Fâtih al-Muzaffar ad-Din with many titles and honorifics. (Inv no.: 37148)

Close-up of rim engraving on Astrolabe with Lunar Mansions, by Abd al-Karim, Jazira (Mesopotamia)?, 1227/8 CE. (Inv no: 37148)

These paeans of praise were not unwarranted: in 1227/8 CE [625 AH] (the year that the astrolabe was made), Al-Ashraf Musa was in the midst of careful negotiations with his brother — al-Kamil, ruler of Egypt — which led to Al-Ashraf expanding the territory under his rule and successfully capturing the city of Damascus in 1229 CE.

As the gold and silver on the astrolabe remain intact, we know that — at the very least — Al-Ashraf Musa liked the object enough to keep its precious metals in place (rather than repurposing them for another object).

In 1425 CE, another ruler also admired the astrolabe enough to keep it intact – or almost.

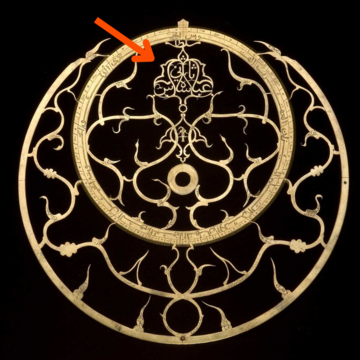

He clearly wished to show the world that this beautiful instrument belonged to him: he had a new rete (or star pointer) made which had his name and title prominently displayed. Today, only the start of the word ‘Sultan’ survives at the top of the rete:

The rete of the astrolabe was added in the year 1425 CE. The beginning of the word ‘Sultan’ is part of the metal work at the top of the rete. (Inv no.: 37148)

Almost 600 years separate us from this ‘new’ addition.

Perhaps at some point in that time there was an accident in which the rete was damaged. Or maybe a more recent owner did not care to have the sultan’s name so prominently displayed – and ripped it off?

This rete is from an astrolabe made in 1647/8 CE. In the top part, you can see the name of the astrolabe's first owner, Shah Abbas II, worked into the design. (Inv no.: 45747)

This rete was added to Al-Ashraf Musa's astrolabe in 1425 CE. In the top part, you can see the beginning of the word 'Sultan' worked into the design. (Inv no.: 37148)

Louise Marie seems to have been happy to leave this question open.

She did not replace the damaged rete – nor did she engrave her name anywhere else on the object.

The Comtesse negotiates with Evans

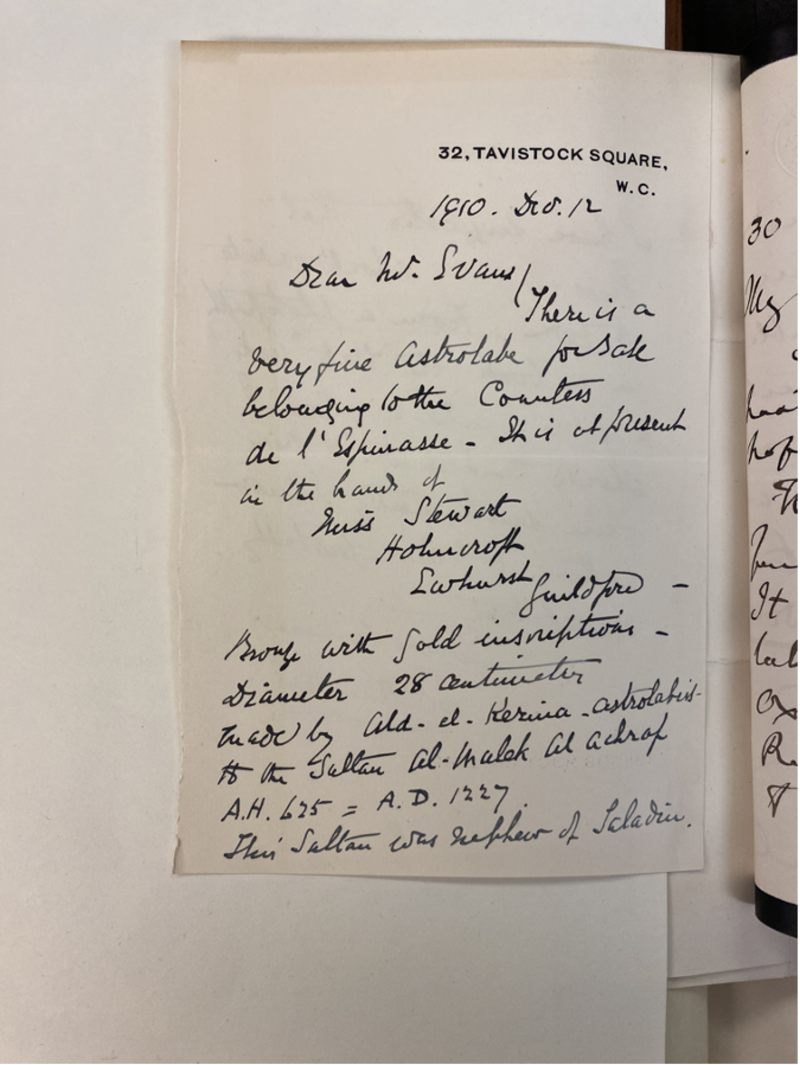

In December 1910, Edward Knobel — Evans’ friend and fellow amateur scholar — wrote to Lewis Evans and notified him that:

There is a very fine astrolabe for sale belonging to the Countess de L’Espinasse [sic].

HSM Evans MS 78. Letter from Edward Knobel to Lewis Evans, written on 12 December 1910 and sent from Knobel’s residence at 32 Tavistock Square, London.

Louise Marie, Comtesse de Lespinasse, died on 21 September 1902 aged 80. Her son and daughter-in-law both died five years later in 1907.

The Lespinasse in correspondence with Knobel was probably Louise Marie’s 23-year-old granddaughter, Odette.

In his letter to Evans, Knobel noted the gold inscriptions, large diameter, and name of the person for whom the astrolabe was made: ‘Sultan Al-Malek Al-Achraf’.

He explained that:

This Sultan was nephew of Saladin

and commented:

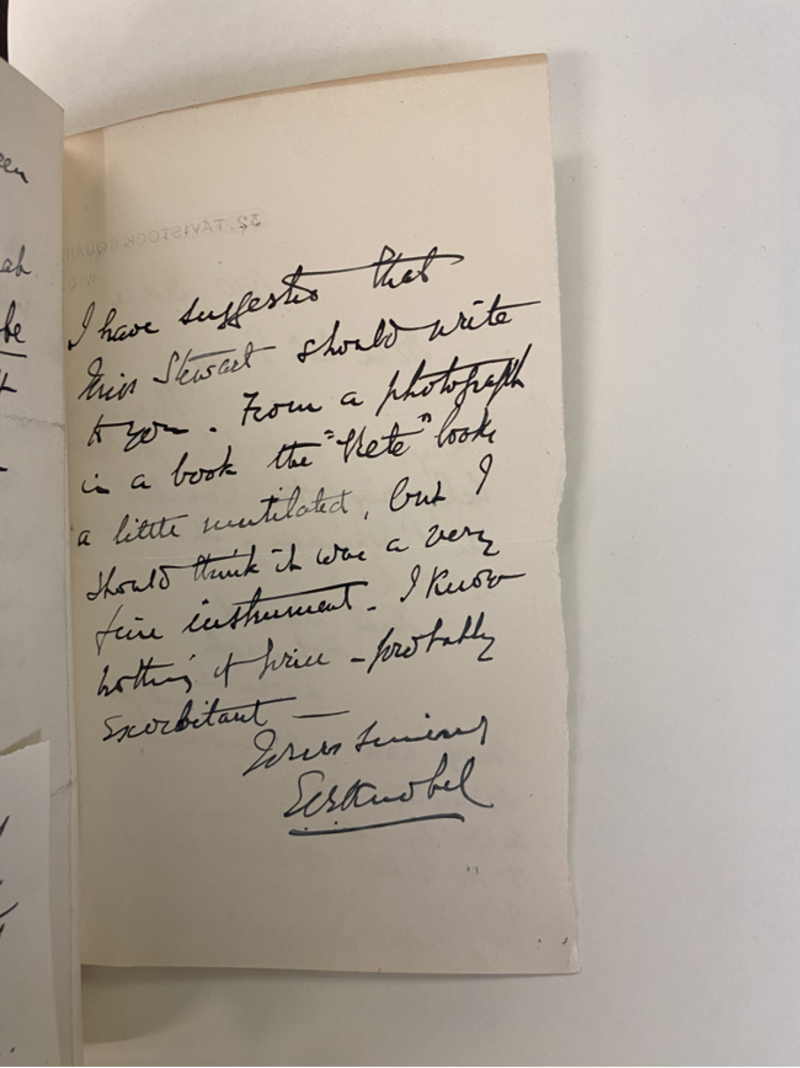

From a photograph in a book the ‘rete’ looks a little mutilated, but I should think it was a very fine instrument, I know nothing of price – probably exorbitant.

HSM Evans MS 78. Letter from Edward Knobel to Lewis Evans, written on 12 December 1910

Evans was quick to act on this information, writing the very next day to Alice Stewart, who was keeping the astrolabe in England for her friend 'Madame de Lespinasse'.

We have the letters that Evans received, not the ones he sent.

From Miss Stewart’s correspondence, it seems that Evans was eager – almost to the point of rudeness – to gain access to the astrolabe.

Miss Stewart, however, would not be pushed about.

Over the course of several months, the astrolabe moved between Knobel’s house in London's Tavistock Square, Miss Stewart’s residence in Guildford, and – finally – the show rooms of The Chelsea Furniture Company in London.

Once the astrolabe arrived at The Chelsea Furniture Company, the negotiation proceeded between Evans and the shop manager. Though it is unclear how many opportunities Evans had to view the astrolabe, Knobel did see it at several points, noting its beauty and historical significance, and urging Evans to up his price.

The Comtesse insisted on £1,000 for the astrolabe.

Evans stuck to his counteroffer of £250.

Ultimately, Evans succeeded with his price.

Was it worth it?

A few years after Evans’ death, Robert Gunther — first Director of the History of Science Museum — wrote that there was another offer for the astrolabe.

In his book Astrolabes of the World (1932), Gunther claimed that some time after Evans had purchased the astrolabe, he was approached by the German Emperor, Wilhelm Hohenzollern. According to Gunther, His Royal Highness wanted to buy the astrolabe, engrave his own coat of arms on it, and take it with him on his travels to the Holy Land.

The emperor offered Evans £800 for the astrolabe.

Evans declined.

What do you think about the negotiation? Would you have paid £1,000 for the astrolabe?

I’d love you to share your thoughts and join the conversation.

October 2023

About the author

Dr Sumner Braund

I’m a historian of early medieval England with a passion for museums and archives.

As Research Fellow on the Finding and Founding Project, I am putting investigative skills to work as I uncover the provenance history of the History of Science Museum’s founding collection.

This work has already taken me to archives in the UK and the US, from nineteenth-century letter collections to sales registers to military dispatches.

For me, history is the study of people – and the objects that I am currently investigating are taking me on a global journey to people past and present.

Share on social media

If you'd like to share this post on social media, just copy this link:

https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/finding-and-founding-blog-three-the-travels-of-...

and go to your chosen social media channel:

Comments

As always, we’re interested to know your thoughts, so please share your comments with me: