Einstein in Oxford

Andrew Robinson, author of Einstein in Oxford (Bodleian, 2024), explores the story behind Einstein's blackboard and the enduring appeal of one of the world's most famous scientists

I rejoice at the new universe to which [Einstein] has introduced us. I rejoice in the fact that he has destroyed all the old sermons, all the old absolutes, all the old cut-and-dried conceptions, even of time and space, which were so discouraging ...

Speech by George Bernard Shaw, 1930

In October 1930, Albert Einstein visited Britain from his home in Germany to attend a charitable fund-raising dinner for disadvantaged East European Jews, given in his honour in London.

There he heard George Bernard Shaw’s words of praise quoted above — part of a speech ‘renowned as one of the finest 20th-century examples of a public eulogy’, according to a recording of it reissued by the British Library in 2005 to celebrate the centenary of Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

The great dramatist and writer clearly placed the great physicist in the pantheon of the immortals, while admitting that he himself had been unable to understand relativity fully, despite his best efforts. According to Shaw, Einstein belonged among the ‘makers of universes’, in the company of Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Aristotle, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton – ‘not makers of empires’ like Alexander and Napoleon.

And when they have made those universes, their hands are unstained by the blood of any human being on earth.

Einstein’s response, spoken in German, mixed genuine humility with typical humour.

I, personally, thank you for the unforgettable words which you have addressed to my mythical namesake, who has made my life so burdensome [yet who] in spite of his awkwardness and respectable dimension, is, after all, a very harmless fellow.

The story of Einstein's blackboard

About six months later, in May 1931, Einstein’s legend accompanied him to Oxford.

He went there as a guest of Christ Church college to give three lectures at Rhodes House on relativity, cosmology and his latest work in physics — and to receive an honorary Oxford doctorate at the Sheldonian Theatre.

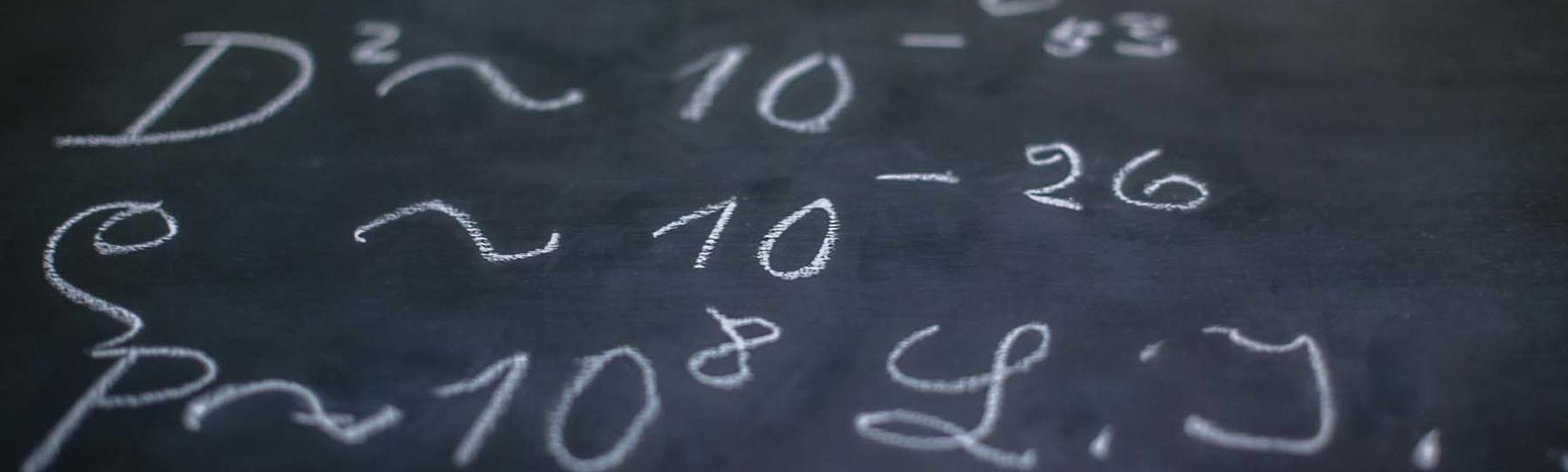

While lecturing, Einstein naturally used equations and diagrams chalked on several blackboards. The second lecture required

two blackboards, plentifully sprinkled beforehand in the international language of mathematical symbol

as The Times reported.

They described the density, size and age of the expanding universe, which Einstein calculated to be ten billion years old.

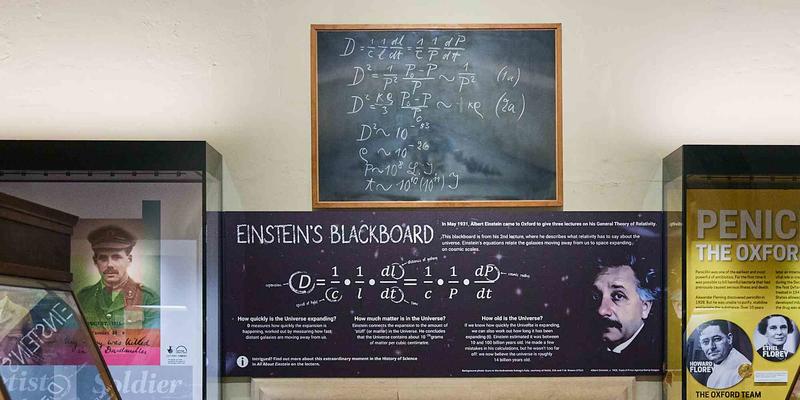

Today, one of those blackboards is the most famous of the 18,000 or so objects in Oxford’s History of Science Museum collections.

Visitors from all over the world come to the Museum especially to view the Einstein blackboard. It is a ‘relic of a secular saint’, as the Museum’s website ironically describes it.

Some visitors today treat it almost as an object of veneration, anxiously requesting its location on arrival and eager to experience some connection with this near-mythical figure of science.

The idea of rescuing and preserving Einstein’s blackboards seems to have come from some Oxford dons who attended his first lecture on 9 May. A memo from the then-warden of Rhodes House to one of the Rhodes trustees, dated 13 May, states plainly that:

Some of the scientists seem to be anxious to secure for preservation in the Museum the blackboard upon which Einstein draws. I was first approached about it by de Beer, who is a fellow of Merton [College], and now Gunther has written to me, asking whether, if it is desired, the blackboard with Einstein’s figures on it may be given to the university.

Gavin de Beer was an embryologist, who became a fellow of the Royal Society and director of the Natural History Museum in London.

Robert Gunther was a zoologist and historian of science, who in 1924 created the nucleus of what became the Museum of the History of Science in 1935.

Yet another Oxford academic involved in the rescue was the chemist Edmund Bowen, also a fellow of the Royal Society, whose laboratory work in photochemistry had confirmed some of Einstein’s theoretical work.

Presumably, they were among the audience on 16 May for the second Rhodes House lecture. Certainly, on 19 May, Gunther formally thanked the secretary of the Rhodes trustees for ‘your present’ to the newly established Museum ‘of two blackboards used by Professor Einstein in his lecture’.

Although one of these blackboards was later accidentally cleaned in the Museum’s storeroom, the other one survived, to be venerated in our time.

Albert Einstein in 1921

Einstein, had he come to know of this accidental erasure of his work, would certainly have laughed, as he loved to do right until the end of his life in 1955.

In May 1931, he was firmly opposed to preserving his blackboards.

Firstly because he regarded them as mere ephemera.

Secondly because they showed work in progress that was almost certain to be superseded by his subsequent calculations.

And lastly because their preservation drew invidious attention to his legendary status.

Hence, on 16 May, after the second lecture, Einstein told his diary with singular annoyance:

The lecture was indeed well-attended and nice. [But] the blackboards were picked up. (Personality cult, with adverse effect on others. One could easily see the jealousy of distinguished English scholars. So I protested; but this was perceived as false modesty.) On arrival [back in Christ Church] I felt shattered. Not even a cart-horse could endure so much!

The informality of genius

In a way, the whole episode of the blackboards – mingling as it did genuinely warm appreciation of the man with relatively superficial understanding of his thought – is typical of Einstein’s experience of Oxford, on his three residences in the city in 1931, 1932 and 1933.

While he clearly enjoyed his personal contact with scientists and a wide range of non-scientists in Oxford – including professional musicians with whom he played his violin – he did not much care either for his legendary status or for the formalities of college and university life, which generally amused and occasionally irritated him.

In his diary, he mocked the dinner-jacketed and gowned dons dining in the ceremonial splendour of Christ Church Hall as the communion ‘of the holy brotherhood in tails’ (‘der heiligen Brüderschaar im Frack’).

He always disliked having to wear formal dress – and even, famously, socks. In a thoughtful and witty poem (now in the Bodleian Library) that he wrote to thank the absent Christ Church don whose college rooms he borrowed in 1931, Einstein called himself, only partly in jest, an old ‘hermit’ and a ‘barbarian’ on the roam.

The language of fame

William Golding at Oxford (1930)

Once, while walking around central Oxford alone as he liked to do, Einstein had a chance encounter with an undergraduate, who had started in science and then changed to literature.

He was William Golding, the future author of Lord of the Flies and Nobel laureate.

Some time in 1931, the young Golding happened to be standing on a small bridge in Magdalen Deer Park looking at the river when a ‘tiny moustached and hatted figure’ joined him.

Professor Einstein knew no English at that time, and I knew only two words of German. I beamed at him, trying wordlessly to convey by my bearing all the affection and respect that the English felt for him.

For about five minutes the two stood side by side.

At last, said Golding,

With true greatness, Professor Einstein realized that any contact was better than none.

He pointed to a trout wavering in midstream. ‘Fisch’, he said.

Golding continues:

Desperately I sought for some sign by which I might convey that I, too, revered pure reason.

I nodded vehemently.

In a brilliant flash I used up half my German vocabulary: ‘Fisch. Ja. Ja.’ I would have given my Greek and Latin and French and a good slice of my English for enough German to communicate.

But we were divided; he was as inscrutable as my headmaster.

For another five minutes, the unknown undergraduate Englishman and the world-famous German scientist stood together.

Then Professor Einstein, his whole figure still conveying goodwill and amiability, drifted away out of sight.

To thine own self be true

As the vivid stories told in Einstein in Oxford reveal, Einstein always stayed true to himself – wherever he roamed, whether it was Britain, Germany, Japan, Palestine, South America or the United States, in which he spent the final two decades of his life.

And this, most probably, is why Einstein still appeals so strongly beyond the world of scientists to the entire globe.

Andrew Robinson is the author of Einstein in Oxford, published by Bodleian Library on 12 September 2024.