Medicine chest

Presented by Sophie Andrews – DPhil candidate in biological sciences

Inventory Number: 53210

Modern medicine can prevent and cure a whole range of illnesses that in times gone by were considered death sentences. Unfortunately, it hasn’t always been this way. In the 19th century – before the development of potent anaesthetics and good hygiene practices – it was much more common and often safer to self-medicate at home.

People would often use medicine chests like the one in our collection to treat their ailments with natural remedies. This chest dates back to around 1820, and is constructed out of mahogany in a style that was very fashionable at the time. However, by far the most interesting part of this item is its contents!

What is kept in a medicine chest?

This box contains a bottle labelled 'Bark Powder'. There were two types of bark powder commonly found in medicine chests. Peruvian bark was a treatment for fevers, and the active ingredient is quinine – which also has antimalarial properties. The other major bark powder was willow bark. This was used as an analgesic and as an anti-inflammatory. Willow bark contains acetylsalicylic acid, which is the active ingredient in aspirin: one of the most widely used pain-relief drugs available today.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZdUtqRc6J1Q

White Willow (Salix alba)

This box also contains turkey rhubarb, which was as a powerful purgative and a laxative. It could also be applied topically to treat fever, by crushing, moistening and applying it directly to the skin as a poultice. Also used as laxatives were castor oil and manna – the sap from flowering ash.

Laxatives were particularly common in medicine boxes like these because the only very powerful painkillers available at the time were opium-based, a well-known example of which is Laudanum. These painkillers very often caused constipation – especially with long-term usage.

Smelling salts also made a regular appearance in medicine chests, and this particular box contains three different types. Smelling salts are made up of ammonium carbonate crystals, and were (and sometimes still are) used for arousing consciousness when someone has fainted. They were obtained by distilling deer bones, horns and hooves to produce an oil, which was then dry distilled to form hartshorn powder. Dissolving this in water or ammonia solution produced spirit sal volatile, which was also used for treating sunstroke and insect bites.

These chests were intended to be used by the average person who would not necessarily have a medical background, so they usually came with instruction manuals, listing the box’s contents, as well as explanations of how they should be used, and in what doses, dependent on factors like age and sex. Once the bottles were empty, they would be refilled and re-labelled by your pharmacist rather than thrown away.

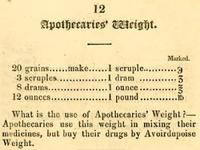

The chests also contained the tools necessary to self-medicate. For example, this box contains a beautiful set of scales to measure out the right amount of medicine, and a complete set of apothecary weights in archaic units such as drams and grains.

Laudanum

Apothecaries’ conversion chart

Medicine chests like these give us insight into the development of modern medicine, and since the 19th century healthcare has changed enormously. There is now a much stronger emphasis on treating the cause of an illness rather than the symptoms, and with greatly improved standards of professional care, we are now more likely to seek pharmaceutical help than self-medicate with natural remedies in the home. However, despite enormous advancements in drug development over the last two centuries, some of the items in this box – or at least, their chemical derivatives – are still used in medicine today.